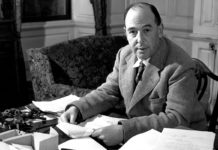

The plush setting was starkly incongruous with the subject I was discussing with Alexander Metherell, MD, PhD. There we were, sitting in the living room of his comfortable California home on a balmy spring evening, warm ocean breezes whispering through the windows, while we were talking about a topic of unimaginable brutality: a beating so barbarous that it shocks the conscience, and a form of capital punishment so depraved that it stands as wretched testimony to man’s inhumanity to man.

I had sought out Metherell because I heard he possessed the medical and scientific credentials to explain the crucifixion. But I also had another motivation: I had been told he could discuss the topic dispassionately as well as accurately. That was important to me, because I wanted the facts to speak for themselves, without the hyperbole or charged language that might otherwise manipulate emotions.

As you would expect from someone with a medical degree (University of Miami in Florida) and a doctorate in engineering (University of Bristol in England), Metherell speaks with scientific precision. He is board certified in diagnosis by the American Board of Radiology and has been a consultant to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health of Bethesda, Maryland.

The Torture Before the Cross

Initially I wanted to elicit from Metherell a basic description of the events leading up to Jesus’ death. So after a time of social chat, I put down my iced tea and shifted in my chair to face him squarely. “Could you paint a picture of what happened to Jesus?” I asked.

He cleared his throat. “It began after the Last Supper,” he said. “Jesus went with his disciples to the Mount of Olives—specifically, to the Garden of Gethsemane. And there, if you remember, he prayed all night. Now, during that process he was anticipating the coming events of the next day. Since he knew the amount of suffering he was going to have to endure, he was quite naturally experiencing a great deal of psychological stress.”

I raised my hand to stop him. “Whoa—here’s where skeptics have a field day,” I told him. “The Gospels tell us he began to sweat blood at this point. Now, c’mon, isn’t that just a product of some overactive imaginations? Doesn’t that call into question the accuracy of the Gospel writers?”

Unfazed, Metherell shook his head. “Not at all,” he replied. “This is a known medical condition called hematidrosis. It’s not very common, but it is associated with a high degree of psychological stress.

“What happens is that severe anxiety causes the release of chemicals that break down the capillaries in the sweat glands. As a result, there’s a small amount of bleeding into these glands, and the sweat comes out tinged with blood. We’re not talking about a lot of blood; it’s just a very, very small amount.”

Though a bit chastened, I pressed on. “Did this have any other effect on the body?”

“What this did was set up the skin to be extremely fragile so that when Jesus was flogged by the Roman soldier the next day, his skin would be very, very sensitive.”

“Tell me,” I said, “what was the flogging like?”

Metherell’s eyes never left me. “Roman floggings were known to be terribly brutal. They usually consisted of thirty-nine lashes but frequently were a lot more than that, depending on the mood of the soldier applying the blows.

“The soldier would use a whip of braided leather thongs with metal balls woven into them. When the whip would strike the flesh, these balls would cause deep bruises or contusions, which would break open with further blows. And the whip had pieces of sharp bone as well, which would cut the flesh severely.

“The back would be so shredded that part of the spine was sometimes exposed by the deep, deep cuts. The whipping would have gone all the way from the shoulders down to the back, the buttocks, and the back of the legs. It was just terrible.”

Metherell paused. “Go on,” I said.

“One physician who has studied Roman beatings said, ‘As the flogging continued, the lacerations would tear into the underlying skeletal muscles and produce quivering ribbons of bleeding flesh.’ A third-century historian by the name of Eusebius described a flogging by saying, ‘The sufferer’s veins were laid bare, and the very muscles, sinews, and bowels of the victim were open to exposure.’

“We know that many people would die from this kind of beating even before they could be crucified. At the least, the victim would experience tremendous pain and go into hypovolemic shock.”

“Do you see evidence of this in the Gospel accounts?”

“Yes, most definitely,” he replied. “Jesus was in hypovolemic shock as he staggered up the road to the execution site at Calvary, carrying the horizontal beam of the cross. Finally Jesus collapsed, and the Roman soldier ordered Simon to carry the cross for him. Later we read that Jesus said, ‘I thirst,’ at which point a sip of vinegar was offered to him.

“Because of the terrible effects of this beating, there’s no question that Jesus was already in serious-to-critical condition even before the nails were driven through his hands and feet.”

The Agony of the Cross

As distasteful as the description of the flogging was, I knew that even more repugnant testimony was yet to come. That’s because historians are unanimous that Jesus survived the beating that day and went on to the cross—which is where the real issue lies.

“What happened when he arrived at the site of the crucifixion?” I asked.

“He would have been laid down, and his hands would have been nailed in the outstretched position to the horizontal beam. This crossbar was called the patibulum, and at this stage it was separate from the vertical beam, which was permanently set in the ground.”

“The Romans used spikes that were five to seven inches long and tapered to a sharp point. They were driven through the wrists,” Metherell said, pointing about an inch or so below his left palm.

“Hold it,” I interrupted. “I thought the nails pierced his palms. That’s what all the paintings show. In fact, it’s become a standard symbol representing the crucifixion.”

“Through the wrists,” Metherell repeated. “This was a solid position that would lock the hand; if the nails had been driven through the palms, his weight would have caused the skin to tear and he would have fallen off the cross. So the nails went through the wrists, although this was considered part of the hand in the language of the day.

“The pain was absolutely unbearable,” he continued. “In fact, it was literally beyond words to describe; they had to invent a new word: excruciating. Literally, excruciating means ‘out of the cross.’ Think of that: They needed to create a new word, because there was nothing in the language that could describe the intense anguish caused during the crucifixion.

“At this point Jesus was hoisted as the crossbar was attached to the vertical stake, and then nails were driven through Jesus’ feet. Again, the nerves in his feet would have been crushed, and there would have been a similar type of pain.”

Crushed and severed nerves were certainly bad enough, but I needed to know about the effect that hanging from the cross would have had on Jesus. “What stresses would this have put on his body?”

Metherell answered, “First of all, his arms would have immediately been stretched, probably about six inches in length, and both shoulders would have become dislocated—you can determine this with simple mathematical equations.

“This fulfilled the Old Testament prophecy in Psalm 22, which foretold the crucifixion hundreds of years before it took place and says, ‘My bones are out of joint.’”

The Cause of Death

Metherell had made his point—graphically—about the pain endured as the crucifixion process began. But I needed to get to what finally claims the life of a crucifixion victim, because that’s the pivotal issue in determining whether death can be faked or eluded. So I put the cause-of-death question directly to Metherell.

“Once a person is hanging in the vertical position,” he replied, “crucifixion is essentially an agonizingly slow death by asphyxiation.

“The reason is that the stresses on the muscles and diaphragm put the chest into the inhaled position; basically, in order to exhale, the individual must push up on his feet so the tension on the muscles would be eased for a moment. In doing so, the nail would tear through the foot, eventually locking up against the tarsal bones.

“After managing to exhale, the person would then be able to relax down and take another breath in. Again he’d have to push himself up to exhale, scraping his bloodied back against the coarse wood of the cross. This would go on and on until complete exhaustion would take over, and the person wouldn’t be able to push up and breathe anymore.

“As the person slows down his breathing, he goes into what is called respiratory acidosis—the carbon dioxide in the blood is dissolved as carbonic acid, causing the acidity of the blood to increase. This eventually leads to an irregular heartbeat. In fact, with his heart beating erratically, Jesus would have known that he was at the moment of death, which is when he was able to say, ‘Lord, into your hands I commit my spirit.’ And then he died of cardiac arrest.”

“Even before he died—and this is important, too—the hypovolemic shock would have caused a sustained rapid heart rate that would have contributed to heart failure, resulting in the collection of fluid in the membrane around the heart, called a pericardial effusion, as well as around the lungs, which is called a pleural effusion.”

“Why is that significant?”

“Because of what happened when the Roman soldier came around and, being fairly certain that Jesus was dead, confirmed it by thrusting a spear into his right side. It was probably his right side; that’s not certain, but from the description it was probably the right side, between the ribs.

“The spear apparently went through the right lung and into the heart, so when the spear was pulled out, some fluid—the pericardial effusion and the pleural effusion—came out. This would have the appearance of a clear fluid, like water, followed by a large volume of blood, as the eyewitness John described in his gospel.”

I pulled out my Bible and flipped to John 19:34. “Wait a minute, Doc,” I protested. “When you carefully read what John said, he saw ‘blood and water’ come out; he intentionally put the words in that order. But according to you, the clear fluid would have come out first. So there’s a significant discrepancy here.”

Metherell smiled slightly. “I’m not a Greek scholar,” he replied, “but according to people who are, the order of words in ancient Greek was determined not necessarily by sequence but by prominence. This means that since there was a lot more blood than water, it would have made sense for John to mention the blood first.”

I conceded the point but made a mental note to confirm it myself later. “At this juncture,” I said, “what would Jesus’ condition have been?”

Metherell’s gaze locked with mine. He replied with authority, “There was absolutely no doubt that Jesus was dead.”

“Is there any possible way—any possible way—that Jesus could have survived this?”

Metherell shook his head and pointed his finger at me for emphasis. “Absolutely not,” he said. “Remember that he was already in hypovolemic shock from the massive blood loss even before the crucifixion started. He couldn’t possibly have faked his death, because you can’t fake the inability to breathe for long. Besides, the spear thrust into his heart would have settled the issue once and for all. And the Romans weren’t about to risk their own death by allowing him to walk away alive.”

“So,” I said, “when someone suggests to you that Jesus merely swooned on the cross . . .”

“I tell them it’s impossible. It’s a fanciful theory without any possible basis in fact.”

Again,” he stressed, becoming a bit more animated, “there’s just no way he could have survived the cross.”

________

Taken from The Case for Christ Movie Edition by Lee Strobel.