In the 19th century, the English language spread its arms across the world and most of the world’s documentation has been recorded with it. Large parts of the world today found themselves in their English-written histories and thereafter took steps to document in their mother tongues. For local consumption and perusal, African art need emphasis in local dialects. If the account of the history of African art is written in languages that are alien to Africa, how do we give credence to African languages?

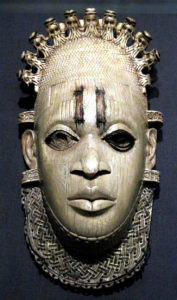

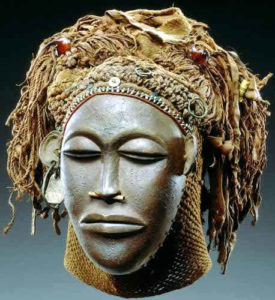

African art has experienced numerous changes and developments from the dynamic and sophisticated philosophies and concettos of different epochs; from the Neolithic settlement of Egypt to the discovery of Nok, Ife, Benin and Igbo-Ukwu, African art has proved to be a living phenomenon. Historically, the art of Africa was a serious obstacle to colonialism as it was deeply rooted in the daily lives of Africans. The colonial masters thereby took the drastic measures of burning, smashing, destroying, and looting the art of Africa. They thereby created another episode of African history through alteration.

African art has experienced numerous changes and developments from the dynamic and sophisticated philosophies and concettos of different epochs; from the Neolithic settlement of Egypt to the discovery of Nok, Ife, Benin and Igbo-Ukwu, African art has proved to be a living phenomenon. Historically, the art of Africa was a serious obstacle to colonialism as it was deeply rooted in the daily lives of Africans. The colonial masters thereby took the drastic measures of burning, smashing, destroying, and looting the art of Africa. They thereby created another episode of African history through alteration.

Prior to the second half of the 19th century, the art of Africa was seen as the art of less value. This was the situation of non-western art until 1897 when Benin looted art objects arrived in England. Its dexterity and craftsmanship stunned European art institutions and led to their acquisitions by individuals and art institutions. This led to the increase in world interest and curiosity to visit Africa and study the works insitu. The result of this was the documentation of African art in languages that are not African.

Contemporarily, specialization is available for the study of African art history. This is a clear roadmap to the documentation of African art in African languages. The suppression of African languages in favour of foreign languages is tantamount to giving out one’s birthright. It is high time we embraced the beautiful and charming languages of Africa as catalysts for growth and development: African languages are vital to the growth and identification of Africa.

The real people of Africa are in the traditional sector and not in the modern sector of the society which is the abode of the elites and the seat of power. They are the men who neglect the comfort of their homes for the survival of an age-long tradition. They set up camps along the roads and receive lullabies from flying birds and snoring animals. Further, they are women who respond to the evolving taste of their environment by changing the physiognomy of their ensemble through tying, dying and weaving. They are women who smoke out their fears in public kilns for the production of functional wares. These are the real people of Africa and their activities inspire external curiosity on African art. The inabilities of these people to access existing literatures of African art question the crucible in which the literatures are formed. If the documentations are primarily about them, why should it remain the subject of discussions among the elites without getting to the real protagonists?

There are over one thousand indigenous languages that elicit joy and pride in the mind of every African on the African continent. These languages synchronize together and reminds Africans of the struggle of their ancestors in search for identity in alien lands after being transported over the Atlantic Ocean. They searched for familiar traits among themselves and reinvented their culture away from home- they thereby presented themselves as embodiments of culture and registered Africa as a force to reckon with in every facet.

There are over one thousand indigenous languages that elicit joy and pride in the mind of every African on the African continent. These languages synchronize together and reminds Africans of the struggle of their ancestors in search for identity in alien lands after being transported over the Atlantic Ocean. They searched for familiar traits among themselves and reinvented their culture away from home- they thereby presented themselves as embodiments of culture and registered Africa as a force to reckon with in every facet.

Africans can only apologise for what they have done and not who they are. They owe no explanation and apology for their culture, why should it be substituted for outside cultures? It is absurd for an outsider to write the story of an insider. Let Africans write and read their stories themselves in languages that are familiar to them.